New Zealand has two recognised languages and both are taught in schools, but not in equal parts – English is taught daily, and from time to time, children learn how to say words and phrases in Maori – the language of the indigenous Maori people. I can greet people (“kia ora“), congratulate them (“ka pai“) or tell them to listen to me (“whakarongo mai“), but because New Zealand is not truly bilingual, these statements are the most I can muster in Maori.

New Zealand students are encouraged to learn a foreign language, and I briefly learned Japanese at high school, but I would be caught out if I travelled to Japan, as I can only remember how to say “もう一度言ってください” (“please say once again”) and “分かりません” (“I do not understand”). These statements in isolation would send a Japanese person into madness if I tried to hold a conversation.

Living in a place like New Zealand, being monolingual is easy – English has 100% saturation throughout the country, and travelling out of our little isolated country is so expensive that many New Zealanders opt to spend their travel dollars heading no further afield than Australia. New Zealanders are generally open to learning a language, and people will choose to take a “language for travellers” class to learn travel language basics before they head to a non-English speaking country, but for many, choosing to travel abroad when you don’t speak the language is firmly placed in what Kiwis call “the too-hard basket”.

My comfortable monolingual existence was turned on its head a few years ago when I travelled to Noumea, New Caledonia. The whirlwind trip was so quickly organised that I had no time to learn any French travel phrases, and oh how I wish I had!

The process of getting through the airport in New Caledonia was free of language barriers – every person in the airport spoke English, all forms were multilingual and the taxi drivers understood us enough to get us to our hotel. As a tourist destination, Noumea is the kind of place that you may be able to get away with no understanding of French if you decide to – if you stick to the strip of beachfront restaurants, only talk to hotel and wait staff, and dance at the nightclubs where other English-speaking people venture, you could get by. But why would you want to?

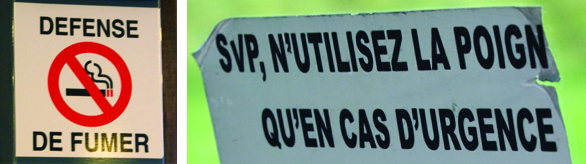

At first, I found French immersion fascinating, and did my best to try and figure out what people were saying and what signs around the place said. Some things were easy to figure out, while others left me wide-eyed and puzzled.

The fun promptly stopped once my group ventured out of the city. We had a tour guide with us who promised us a superb drive through the forest and a lovely meal at a secluded restaurant, and he was right – the trip out of the main centre was beautiful, the scenery breathtaking, and the stops we took along the way showed us how the indigenous Kanak people live, work and eat.

The restaurant itself was a traditional French restaurant, and with the wait staff only speaking French, I had to trust our tour guide to make our order for us. When our guide explained to the waiter that I was a vegetarian, a conversation began where the pair gestured at me and laughed a few times. I would later find out that the waiter had made a joke at my expense, saying something along the lines of “vegetarians don’t know good food anyway”. When lunch arrived, everyone’s eyes bulged out of their heads – the table was laden with tenderised steak, chicken soup, spinach and mushroom galettes, and potato croquettes. My plate came out last, and my eyes bulged for a different reason. I was given a something resembling what you would feed a rabbit – a bed of lettuce, four slices of tomato and a mountain of grated carrot.

The restaurant itself was a traditional French restaurant, and with the wait staff only speaking French, I had to trust our tour guide to make our order for us. When our guide explained to the waiter that I was a vegetarian, a conversation began where the pair gestured at me and laughed a few times. I would later find out that the waiter had made a joke at my expense, saying something along the lines of “vegetarians don’t know good food anyway”. When lunch arrived, everyone’s eyes bulged out of their heads – the table was laden with tenderised steak, chicken soup, spinach and mushroom galettes, and potato croquettes. My plate came out last, and my eyes bulged for a different reason. I was given a something resembling what you would feed a rabbit – a bed of lettuce, four slices of tomato and a mountain of grated carrot.

At this very moment, the powerlessness of not knowing the language hit me. I couldn’t tell the waiter that many items on the plates of my fellow diners were vegetarian, and I couldn’t ask to be served anything else without bothering my tour guide as he happily ate; I was left to eat what I was given while the others feasted on the rich delicacies in front of them. I was thankfully spared a few croquettes and half a galette by the others at the table, but I decided then and there that I would eat seafood for the remainder of the trip. I asked my tour guide to teach me the words “poisson” and “crevettes” and “merci beaucoup” so that I could scour the menu and order on my own without bothering him. Even though I still couldn’t properly communicate with waiters, it was better than having to deal with rabbit food again!

My first week at LAT Multilingual coincided with the first week of online language classes, and staff were given the option of learning Beginners Mandarin, scrubbing up on Conversational French or learning Beginners French. I positively jumped at the chance to take Beginners Class. After one class I can already greet my French colleagues – even if my voice rises at the end of every word as if I’m asking a question. Here’s hoping I can get back to Noumea sometime and do all the ordering on my own!